Speak to me in a language I can hear

Kikoemasuka?

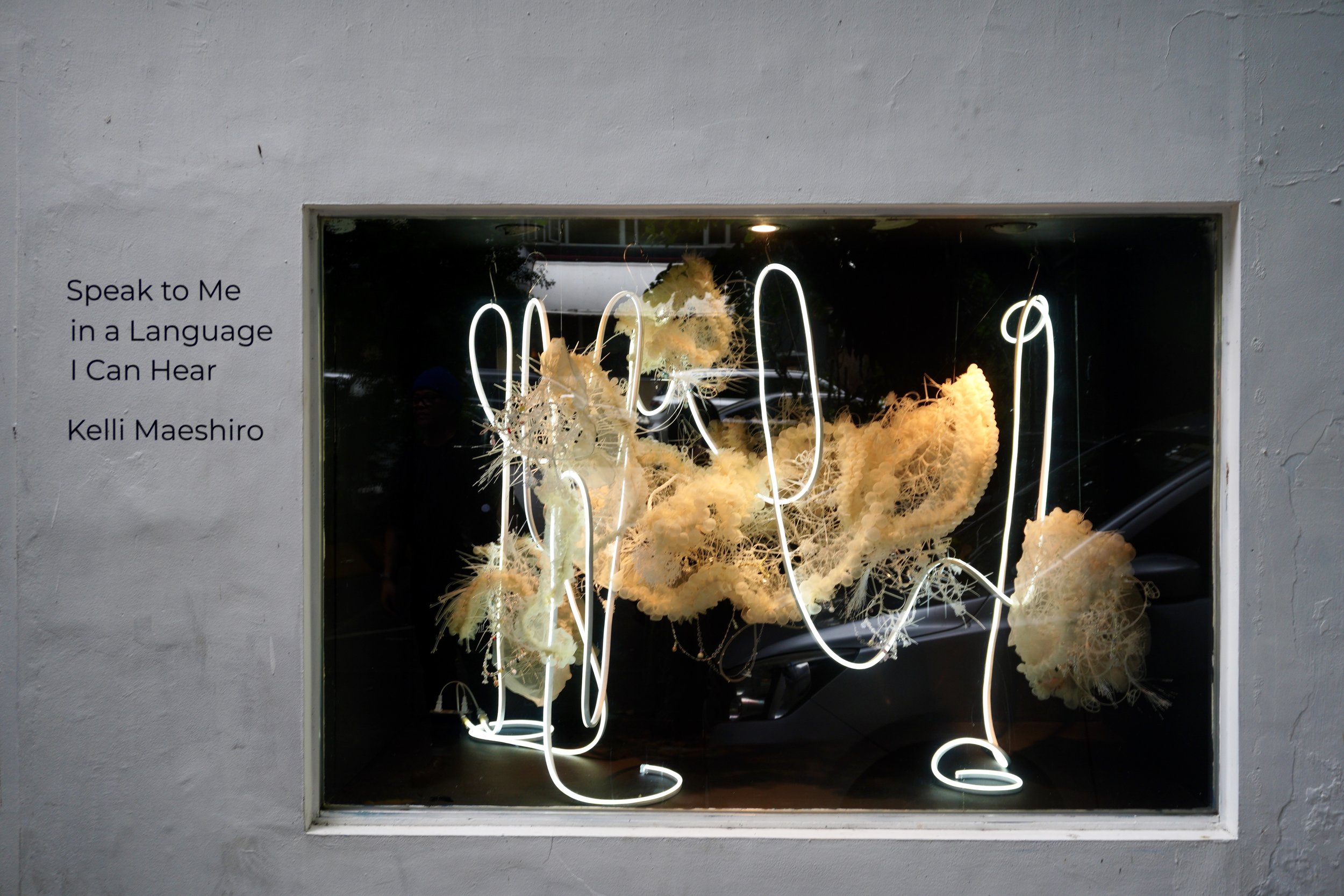

In such a small space, at least by most gallery or exhibition standards, Kelli Maeshiro opens up a world of dialogue and expression with “Speak to me in a language I can hear.”

A soft sculpture occupies, and in itself creates a space of longing and discovering. Being a conglomerate of various materials that are products of searching and researching, it evokes a vitality, a movement – as if it were a living, breathing creature. Against the darkness and solitude imposed upon it by its site, the viewer perhaps ponders their own state.

The series derives from works that the artist brought in her first sojourn to Manila, which were long scroll drawings. From their unintentional narratives, which were anchored on her search for materials, the ritual evolved into the creation of these three-dimensional drawings. More synthesized over prolonged practice – rather than idly stumbling upon – these works are also built upon the search: for the self, for the space, for her biological mother. The artist’s search builds her visual language, with which she converses with the viewer. Whatever knowledge, whatever secrets uncovered dissipate into its endless undulations.

Among the countless forms that the work appears to viewers as, the most popular is of the Cnidarian – jellyfish if you will. In fact, any cursory glance at the work brings to mind the animal by way of association with body parts. “Oh, that’s a tentacle!” “Those globules must be some kind of protection.” “Wow, look at all those creatures caught in the arms!” Nevertheless, that tender, floating piece of visceral flesh is the perfect metaphor for the artist’s search. Slowly travelling in soft movements through time, caught in a cycle of living and life. Some jellyfish are thought of as immortal, but they shed all the baggage of their current existence until they are at their most primal form. They do not die, but they go through the cycle again. For however long, they search and collect, memories becoming markings like DNA. A glimpse here and there captures minute details that she worked into the overall muted canvas of tendrils and tongues.

Speaking of tongues, the work means to speak in volumes; not just in shape and expanse, but in a language both coded yet intelligible. It creaks and rustles like a bamboo forest swaying with the wind. It whispers like the mountain in your ears while on a bicycle downhill, passing by rivers and rice fields. It is loud and immense, and at the same time, soft and forgetting.

Be it in gratitude, self-discovery, or homage, for Kelli Maeshiro, there is no fear in the search. As it expands, it also illuminates; it accumulates and it beckons: speak to me in a language I can hear, for you are the one who understands the language that I exist in.